Mystic Gambler

Page 3 of 3

Back to Page 2 | Back to Page 1

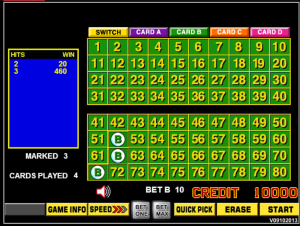

Gambler's grille - mystic lake prior lake. gamblers grille prior lake. gamblers grille mystic lake prior lake. mystic lake gambler's grill prior lake. How to set up Four Card Keno and to play the Mystic 3 spot allowing you to play longer, catch more jackpots simultaneously on all four cards and have more fu. Mystic Gambler Baccarat Game free. download full casino with all the opportunities Mystic Gambler Baccarat Game free. download full that we mentioned earlier, is the option to play anywhere, anytime, no matter where you are or what time, since being online and have a 24 / 7 there are no limits. Formerly “The Mystic Gambler”. By The Magic Gambler. Exciting, All New Keno and Video Poker Games From IGT Corporation. By The Magic Gambler.

VII. CONCLUSION

The data and the arguments presented in this thesis constitute an extended circumambulation of the image of 'magician' in the human psyche. Perhaps the examples of magicians and their tools which have been discussed will find some echo in the psyche of the reader. Perhaps, too, the suggestions of ways in which analysts are magicians will prove stimulating to those working in this field.164 In the final analysis, however, there remains something mysterious about the psyche and its images just as with magic and magicians. I began this thesis with a reference to my father taking me as a boy to the meetings of the International Brotherhood of Magicians. Let me end with another personal story.

I first visited Zürich in the summer of 1961, just after Jung had died. I went to the Jung Institute on the Gemeindestrasse, the very building where I have now lived for the past two years, but somehow I was afraid to enter. 'What would I say?' I asked myself. Many years later I returned to Zürich and visited the Institute, which by this time had moved to Küsnacht. This time I arranged interviews with several Zürich analysts to discuss my interest in the training program. One of these was Dr. Hilde Binswanger. We spent an hour discussing the training program at the Institute and my insecurities about giving up my career as a philosophy professor to enter it, feeling somehow embarrassed about making such a major change in my life. Finally she said to me: 'Jung used to say, 'Follow your Schlange, follow your snake.'

Thompkins, also known as Lottie Deno (April 21, 1844 – February 9, 1934), was a famous gambler in the US state of Texas and New Mexico during the nineteenth century known for her poker skills as well as her courage. She was born in Kentucky and traveled a great deal in her early adulthood before coming to Texas.

I took her advice, and my ÆSchlangeØ led me back and forth between America and Zürich for many years until now I find myself at the end of this training program. During my ten semesters of training I never found a passage where Jung wrote about 'following one's snake,' but then just as I was finishing this thesis I noticed a reference in the index to Jung's Collected Works under 'wand, magic': 'see also caduceus' that is, the magic wand of Hermes, Asclepius and others. And in looking this up I found the following passage, with which I end this thesis:

... the right way to wholeness is made up, unfortunately, of fateful detours and wrong turnings. It is a longissima via, not straight but snakelike, a path that unites the opposites in the manner of the guiding caduceus, a path whose labyrinthine twists and turns are not lacking in terrors.165 And in rewards.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ashe, Geoffrey. 'Merlin in the Earliest Records,' in The Book of Merlin. London: 1988, pp. 31-42.

Bandler, Richard, and John Grinder. ReFraming: Neuro-Linguistic Programming and the Transformation of Meaning. Moab, UT: Real People Press, 1982.

Bandler, Richard, and John Grinder. The Structure of Magic. Science and Behavior Books, 1975.

Benít's Reader's Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

Betz, Hans Dieter, ed. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Blau, Ludwig. Das Altjüdische Zauberwesen. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1974.

Brandon, Ruth. The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini. London: Secker & Warburg, 1993.

Burger, Eugene. The Experience of Magic. New York: Kaufman and Greenberg, 1989.

Burger, Eugene, and Robert E. Neale. Magic and Meaning. Seattle, WA: Hermetic Press, 1995.

Campbell, Joseph. The Power of Myth. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Campbell Joseph, and Richard Roberts. Tarot Revelations. San Anselmo, CA: Vernal Equinox Press, 1979.

Catalogo del Museo Sacro IV. Vatican City: Vatican Publications, 1959, Catalog 31.

Charles, Lucile H. 'Drama in Shaman Exorcism,' Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 66, No. 260 (April-June 1953), pp. 95-122.

Christopher, Milbourne. The Illustrated History of Magic. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1973.

Clarke, J.J. In Search of Jung: Historical and Philosophical Enquiries. London: Routledge, 1992.

Cohen, Edmund D. C.G. Jung and the Scientific Attitude. Totowa, NJ: Littlefield, Adams & Co., 1976.

Concise Columbia Encyclopedia. New York: Avon Books, 1983.

Cooper, J.C. An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

Crow, W.B. A History of Magic, Witchcraft and Occultism. London: Sphere Books, 1972.

de Givry, Grillot. Witchcraft, Magic & Alchemy, translated by J. Courtenay Locke. New York: Dover Publications, 1971.

de Vries, Ad. Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., 1976.

Drury, Nevill. The Shaman and the Magician: Journeys Between the Worlds. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982.

Edsman, Carl-Martin. ed. Studies in Shamanism. Stockholm: Almquist and Wiksell, 1967.

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.

Ellenberger, Henri F. The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: Macmillan, 1922.

Gabriel, Mariann Baskin. 'Using the Shamanic Journey in Psychotherapy,' Shamanic Applications Review: A Journal of Religious Resources in Psychotherapy, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Fall 1995), pp. 47-51

Gad, Irene. Tarot and Individuation: Correspondences with Cabala and Alchemy. York Beach, ME: Nicolas-Hays, 1994.

Gallo, Ernest. 'Synchronicity and the Archetypes,' Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Summer 1994), pp. 396-403.

Gollnick, James. 'Merlin as Psychological Symbol: A Jungian View' in James Gollnick, ed. Comparative Studies in Merlin from the Vedas to C.G. Jung. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1991, pp. 111-131.

Goodrich, Leona. Merlin. New York, 1987.

Habiger-Tuczay, Christa. Magie und Magier im Mittlealter. München: Diederichs, 1992.

Haich, Elisabeth. The Wisdom of the Tarot. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1975.

Handw¾rterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens. Berlin: 1927.

Harner, Michael. The Way of the Shaman. New York: Harper & Row, 1990.

Hastings, James, ed. Encyclopådia of Religion and Ethics. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1926.

Herder Symbol Dictionary, translated by Boris Matthews. Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications, 1986.

Hill, G., ed. The Shaman from Elko. San Francisco: C.G. Jung Institute of San Francisco, 1978.

Hillman, James. Revisioning Psychology. New York: Harper and Row, 1975.

Homer's Odyssey, translated by Robert Fitzgerald. New York: Anchor Books, 1963.

Jaffí, Aniela. 'Was C.G. Jung a Mystic?' and Other Essays. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag, 1989.

Jacoby, Mario. 'Die Archetypen,' Du: Die Zeitschrift der Kultur, No. 8 (August 1995), pp. 27-34.

Jung, C.G. 'A Talk with Students at the Institute,' in William McGuire and R.F.C. Hull, eds. C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977, pp. 359-364.

Jung, C.G. 'A Study in the Process of Individuation,' Collected Works [Hereafter 'CW']. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953-1979. Vol. 9i, para. 525-626.

Jung, C.G. 'Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious,' CW 9i, para. 1-86.

Jung, C.G. 'Concerning Mandala Symbolism,' CW 9i, para. 627-712.

Jung, C.G. 'Concerning the Archetypes, with Special Reference to the Anima Concept,' CW 9i, para. 111-147.

Jung, C.G. 'Definitions,' Psychological Types. CW 6, para. 672-844.

Jung, C.G. 'On the Psychology of the Trickster-Figure,' CW 9i, para. 456-488.

Jung, C.G. 'On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,' CW 15, para 97-132.

Jung, C.G. 'Psychological Aspects of the Mother Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 148-198.

Jung, C.G. 'Religion and Psychology: A Reply to Martin Buber,' CW 18, para. 1499-1513:

Jung, C.G. 'The Psychology of the Child Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 259-305.

Jung, C.G. 'The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales,' CW 9i, para. 384-455.

Jung, C.G. 'The Mana-Personality,' CW 7, para. 374-406.

Jung, C.G. 'The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious.' CW 7, para. 141-191.

Jung, C.G. 'Transformation Symbolism in the Mass,' CW 11, para. 296-448.

Jung, C.G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. CW 9ii.

Jung, C.G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. London: Fontana Press, 1995.

Jung, C.G. Letters, Vol. 1 (1906-1950). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Jung, C.G. Letters, Vol. 2 (1951-1961). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Jung, C.G. Psychology and Alchemy, CW 12.

Jung, C.G. The Tavistock Lectures, CW 18, para. 1-415.

Kalshed, Donald. Lecture, 'ÆFitcher's BirdØ and the Dark Side of the Self,' Zürich Jung Institute, February 22, 1994.

Kaplan, Aryeh. Sefer Yetzirah: The Book of Creation In Theory and Practice. York Beach, ME: Weiser, 1990.

Kaplan, Stuart. The Encyclopedia of Tarot. New York: U.S. Games Systems, 1978.

Kast, Verena. The Dynamics of Symbols: Fundamentals of Jungian Psychotherapy. New York: Fromm International, 1992.

Kaster, Joseph. Putnam's Concise Mythological Dictionary. New York: Perigee Books, 1990.

Kerínyi, Karl. Hermes, Guide of Souls. Dallas: Spring Publications, 1986.

King, Anne. 'Dedi Revisited,' The Magic Circular (Magazine of the Magic Circle of London), Vol. 89, No. 957 (October 1995), pp. 182-184.

King, Francis. Magic: The Western Tradition. London: Thames and Hudson, 1975.

Lantiere, Joe. The Magician's Wand: An Illustrated History. Oakville, CT: Joe Lantiere Books, 1990.

Lippross, Otto. Logik und Magie in der Medizin. München: J.F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1969.

Lockhart, Russell A. Words as Eggs: Psyche in Language and Clinic. Dallas: Spring Publications, 1983.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. Magic, Science and Religion. New York: Anchor Books, 1954.

Marlin, Michael. 'Magic with a Capital 'M,' Magic: The Independent Magazine for Magicians, Vol. 5, No. 4 (December 1995), pp. 26-27.

Mauss, Marcel. A General Theory of Magic. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.

Maven, Max. Max Maven's Book of Fortunetelling. New York: Prentice Hall, 1992.

McGowan, Don. What Is Wrong with Jung. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1994.

Merritt, Dennis L. 'Jungian Psychology and Science A Strained Relationship,' The Analytic Life. Boston: Sigo Press, 1989, pp. 11-31.

Mertz, Bernd. Kartenlegen: Wahrsagen mit Tarot-, Skat-, Lenormand- und Zigeunerblìttern. Niederhausen: Falken, 1985.

Micha, Alexandre. ?tude sur le 'Merlin' de Robert de Boron. Geneva, 1980.

Moore, Robert, and Douglas Gillette. The Magician Within: Accessing the Shaman in the Male Psyche. New York: Avon Books, 1994.

Müller, Lutz. Magie: Tiefenpsychologischer Zugang zu den Geheimwissenschaften. Stuttgart: Kreuz Verlag, 1989.

Mulholland, John. Magic of the World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1965.

Nagy, Marilyn. Philosophical Issues in the Psychology of C.G. Jung. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991.

Neale, Bob. 'The Gifts of McBride,' M-U-M (Magazine of the Society of American Magicians), Vol. 84, No. 11, April 1995.

Newman, Kenneth D. The Tarot: A Myth of Male Initiation. New York: Quadrant, 1983.

Nichols, Sallie. Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1980.

Noll, Richard. The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Oxford Companion to the Bible, Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Oxford Companion to English Literature, 5th ed., Margaret Drabble, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Pearson, Carol S. Awakening the Heroes Within. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1991.

Pennick, Nigel. Secret Games of the Gods: Ancient Ritual Systems in Board Games. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1989.

Radin, Paul. The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology. London: 1956.

Randi, James. Conjuring. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992.

Regardie, Israel. The Middle Pillar: A Co-Relation of the Principles of Analytical Psychology and the Elementary Techniques of Magic. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1970.

R¢heim, Gíza. Magic and Schizophrenia. New York: International Universities Press, 1955.

Russell, Jeffrey B. A History of Witchcraft, Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans. London: Thames and Hudson, 1980.

Salverte, Eusebe. The Philosophy of Magic. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1847.

Samuels, Andrew, Bani Shorter and Fred Plaut. A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986.

Segaller, Stephen, and Merrill Berger. The Wisdom of the Dream: The World of C.G. Jung. Boston: Shambhala, 1989.

Shapiro, A.K. 'The Placebo Effect in the History of Medical Treatment: Implications for Psychiatry' (1959), quoted in Jerome D. Frank and Julia B. Frank. Persuasion and Healing, 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1933.

Sjoo, Monica, and Barbara Mor. The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth. New York: Harper and Row, 1987.

Smith, Morton. Jesus the Magician. New York: Harper, 1978.

Smith, Richard F. Prelude to Science: An Exploration of Magic and Divination. New York: Scribner's Sons, 1975.

Spiegelman, J. Marvin. 'Active Imagination: Values, Limitations, and Potentialities for Further Development,' Harvest, No. 27 (1981), pp. 81-89.

Spiegelman, J. Marvin. 'Psychology and the Occult,' Spring (1976), pp.

Stapleton, Michael. The Illustrated Dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology. New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1986.

Stevens, Anthony. Archetypes: A Natural History of the Self. New York: Quill, 1982.

Lívi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

Taylor, Rogan. The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar. London: Anthony Blond, 1985.

Tolstoy, Nikolai. The Quest for Merlin. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985.

von Franz, Marie-Louise. C.G. Jung: His Myth in Our Time. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1975.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot: Being Fragments of a Secret Tradition under the Veil of Divination. New York: University Books, 1959.

Wassner, Rainer. Magie und Psychotherapie: Ein gesellschaftswissenschaftlicher Vergleich von Institutionen der Krisenbewìltigung. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1984.

Whaley, Bart. Who's Who in Magic: An International Biographical Guide from Past to Present. Wallace, ID: Jeff Busby Magic, 1991.

Wier, Dennis R. Trance: from magic to technology. Ann Arbor, MI: Trans Media, 1996.

Mystic Gambler 6 Spot

Willeford, William. The Fool and His Scepter. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1969.

Windholz, George. 'Bleuler's Views on Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics and on Psi Phenomena,' Skeptical Inquirer (Journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal), Vol. 18, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 273-279.

Whitmont, Edward. 'Magic and the Psychology of Compulsive States,' The Journal of Analytical Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1957), pp. 3-32.

Zimmer, Heinrich. 'Merlin' Corona, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1939), pp. 133-155.

About the Author

John Granrose was born in 1939 in Miami, Florida. He received his B.A. in philosophy and psychology from the University of Miami, studied at the University of Heidelberg on a U.S. Fulbright Grant, and received his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Michigan in 1966. His doctoral dissertation, 'The Implications of Psychological Studies of Conscience for Ethics,' dealt with the theories of Freud, Piaget, and B.F. Skinner.

From 1966 until 1993, he taught in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Georgia. He has also taught at the University of Miami and the University of Michigan and has held visiting professorships at Keele University in England and the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany. Since 1993 he has been Professor Emeritus of Philosophy in the University of Georgia.

His work has been published in the Harvard Theological Review, the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, the Journal of Social Philosophy, Business and Professional Ethics, and other journals. He is the co-editor of Introductory Readings in Ethics (Prentice-Hall, 1974) and the co-author of Practical Business Ethics (Prentice-Hall, 1995).

Dr. Granrose is a member of the American Philosophical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the Society for Values in Higher Education.

Ring the bells that still can ring.

Forget your perfect offering.

There is a crack in everything.

That's how the light gets in.

-- Leonard Cohen

FOOTNOTES

1 These general, intellectual issues about magic are explored in many existing publications. Especially recommended are: James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (New York: Macmillan, 1922); Marcel Mauss, A General Theory of Magic (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972), first published, in French, in 1950; Eusebe Salverte, The Philosophy of Magic (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1847), first published, in French, in 1829.

2 My father, Sylvester Granrose, was born in Helsinki in 1895, went to the United States with his parents and sister when he was five years old, and died in Miami in 1958. At the time of his death I was 18. He was an athlete, representing the U.S. in the 1920 Olympic Games, and eventually became a professional swimming teacher. Performing 'magic tricks' was his life-long avocation.

3 Dream from August 29, 1995, used with permission. My translation.

4 Since I do not return to this general question of magic in history and in different cultures later in this thesis, I mention several important sources here for the interested reader: Works by conjurors: Milbourne Christopher, The Illustrated History of Magic (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1973). John Mulholland, Magic of the World (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1965). James Randi, Conjuring (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992). Works by academic scholars: W.B. Crow, A History of Magic, Witchcraft and Occultism (London: Sphere Books, 1972). James Hastings (ed.), Encyclopådia of Religion and Ethics (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1926), article on Magic, Vol. 8, pp. 245-321. Francis King, Magic: The Western Tradition (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975). Jeffrey B. Russell, A History of Witchcraft, Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980).

5 See, for example, Jung's remarks in 'Religion and Psychology: A Reply to Martin Buber,' CW 18, para. 1506-1507: It should not be overlooked that what I am concerned with are psychic phenomena which can be proved empirically to be the bases of metaphysical concepts, and that when, for example, I speak of 'God' I am unable to refer to anything beyond these demonstrable psychic models which, we have to admit, have shown themselves to be devastatingly real. ... The 'reality of the psyche' is my working hypothesis, and my principal activity consists in collecting factual material to describe and explain it.

6 Two articles worth reading are: Ernest Gallo, 'Synchronicity and the Archetypes,' Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Summer 1994), pp. 396-403; and Dennis L. Merritt, 'Jungian Psychology and Science A Strained Relationship,' The Analytic Life (Boston: Sigo Press, 1989), pp. 11-31.

7 'Psychological Aspects of the Mother Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 154.

8 'Concerning the Archetypes and the Anima Concept,' CW 9i, para. 136.

9 For a review of these discussions, plus a sympathetic and plausible account of the nature and origins of archetypes, see Anthony Stevens, Archetypes: A Natural History of the Self (New York: Quill, 1982). A brief account in German is given in Mario Jacoby, 'Die Archetypen,' Du: Die Zeitschrift der Kultur, No. 8 (August 1995), pp. 27-34. For interesting yet unsympathetic accounts, see Don McGowan, What Is Wrong with Jung (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1994), pp. 63-87, and Richard Noll, The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), pp. 40-43.

10 For example: 'The magician is the archetype behind a multitude of human professions and 'callings.' Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, The Magician Within (New York: Avon Books, 1993), p. 63. Also, in discussing archetypes as links with the past, Jung mentions 'the preoccupation of the primitive mentality with certain 'magic' factors, which are nothing less than what we would call archetypes. 'The Psychology of the Child Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 271.

11 'The Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious.' CW 7, para. 153, 154.

12 CW 7, para. 143.

13 CW 7, para. 157.

14 In addition to Anthony Stevens' excellent book Archetypes, cited earlier, there is a detailed discussion of these issues in Marilyn Nagy, Philosophical Issues in the Psychology of C.G. Jung (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), pp. 107-203. A briefer discussion is found in Edmund D. Cohen, C.G. Jung and the Scientific Attitude (Totowa, NJ: Littlefield, Adams & Co., 1976), pp. 29-38. J.J. Clarke, In Search of Jung: Historical and Philosophical Enquiries (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 116-127, also considers these issues carefully. Finally, some related views of Jung's Burgh¾lzli colleague Eugen Bleuler are interestingly discussed in George Windholz, 'Bleuler's Views on Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics and on Psi Phenomena,' Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 18, No. 3, Spring 1994, pp. 273-279.

15 The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1933), Vol. II, p. 2108.

16 Verena Kast, The Dynamics of Symbols: Fundamentals of Jungian Psychotherapy (New York: Fromm International, 1992), p. 10.

17 'On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,' CW 15, para 105.

18 Andrew Samuels, Bani Shorter and Fred Plaut, A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), pp. 145-6.

19 For further discussion of this see 'The Two Magics' in Eugene Burger, The Experience of Magic (New York: Kaufman and Greenberg, 1989), pp. 81-90. For an even more elaborate taxonomy of magic(s), see Robert Neale's chapter 'Many Magics' in Eugene Burger and Robert E. Neale, Magic and Meaning (Seattle, WA: Hermetic Press, 1995), pp. 173-189. One simple distinction between two kinds of magic is: There is magic (with a little 'm'): one person knows how it is done, but nobody else does. There is Magic (with a capital 'M'): nobody knows how it is done; it just happens! Michael Marlin, 'Magic with a Capital 'M,' Magic: The Independent Magazine for Magicians, Vol. 5, No. 4 (December 1995), p. 26.

20 It should perhaps be noted that the approach taken in a research paper or thesis of the present sort is only one way working with our image(s) of the magician. Active imagination, for example, would lead in other directions. In any case, the limitations of the 'academic' should be kept in mind lest we mistake the map for the territory. As Hillman writes: 'We sin against imagination whenever we ask our image for its meaning, requiring that images be translated into concepts. [James Hillman, Revisioning Psychology (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), p. 39.]

21 For example, in 'Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious,' CW 9i, para. 71-77, as well as in several other places.

22 James Hastings (ed.), Encyclopådia of Religion and Ethics (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1930), Vol. 8, p. 245. The derivation in other languages may differ, of course. In Slavic languages, for example, the Indo-European root wer, meaning 'to speak,' became a word meaning 'to lie,' then a word meaning 'magician,' and then a word meaning 'physician. The progression is interesting. See Russell A. Lockhart, Words as Eggs: Psyche in Language and Clinic (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1983), p. 100.

23 Ludwig Blau, Das Altjüdische Zauberwesen (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1974), pp. 23-26.

24 The entry 'Witch' in The Oxford Companion to the Bible, Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 805, contains the following: Several Hebrew terms are associated with the English word 'witch. These can be translated 'sorcerer,' 'sorceress,' 'medium,' or 'necromancer. Most appear in references to prohibited practices (e.g., Deut. 18:9-11; 2 Kings 23:24) and seem to be concerned with divination or necromancy. Women may have been especially involved in such activities since they were excluded from those of the official cult.

25 Nikolai Tolstoy, The Quest for Merlin (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1985), pp. 19-20.

26 'On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena,' CW 1, para. 1-150.

27 J. Marvin Spiegelman, 'Psychology and the Occult,' Spring (1976), p. 116.

28 'The Mana-Personality,' CW 7, para. 374-406.

29 Andrew Samuels, Bani Shorter and Fred Plaut, A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 89.

30 CW 7, para. 388.

31 CW 7, para. 377.

32 The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia (New York: Avon Books, 1983), p. 768.

33 Michael Harner, The Way of the Shaman (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990). First published in 1980. In his preface to the 1990 edition of this book, Harner writes: Ten years have passed since the original edition of this book appeared, and they have been remarkable years indeed for the shamanic renaissance. Before then, shamanism was rapidly disappearing from the Planet as missionaries, colonists, governments, and commercial interests overwhelmed tribal peoples and their ancient cultures. During the last decade, however, shamanism has returned to human life with startling strength, even to urban strongholds of Western 'civilization,' such as New York and Vienna. (p. xi)

34 Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964), p. 3.

35 Eliade, p. 5.

36 Jung thought, for example, that it was in states such as this that myths were originally formed. See 'The Psychology of the Child Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 264.

37 This is the subject of an excellent new book: Dennis R. Wier, Trance: from magic to technology (Ann Arbor, MI: Trans Media, 1996.

38 For discussion of this see Nevill Drury, The Shaman and the Magician: Journeys Between the Worlds (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982).

39 C.G. Jung: His Myth in Our Time (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1975), p. 99.

40 C.G. Jung, Letters, Vol. 1 (1906-1950), (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), p. 377. Letter of August 20, 1945, to P.W. Martin.

41 In a story told by Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig in Stephen Segaller and Merrill Berger, The Wisdom of the Dream: The World of C.G. Jung (Boston: Shambhala, 1989), p. 85.

42 Rogan Taylor, personal communication. My thanks to him.

43 Marie-Louise von Franz, personal communication. My thanks to her. This story is also reported in Rogan Taylor, The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar (London: Anthony Blond, 1985), p. 146. Note, in this connection, that the ÆFestschriftØ for Jungian analyst Joseph Henderson is called The Shaman from Elko.

44 CW 9i, para. 456-488.

45 Paul Radin, with commentaries by C.G. Jung and Karl Kerínyi (Zürich: 1954). English version: The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology (London: 1956).

46 'On the Psychology of the Trickster-Figure,' CW 9i, para. 484.

47 CW 9i, para. 457.

48 One is reminded here of Nietzsche's aphorism: 'Nothing succeeds unless prankishness has a part in it.'

49 CW 9i, para. 472.

50 William Willeford, The Fool and His Scepter (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1969).

51 Willeford, p. xxi.

52 Willeford, p. 88.

53 See, for example, the entry 'Hermes' in Michael Stapleton, The Illustrated Dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology (New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1986), p. 104.

54 From Joe Lantiere, The Magician's Wand: An Illustrated History (Oakville, CT: Joe Lantiere Books, 1990), p. 18.

55 As Robert Fitzgerald translates the passage at the beginning of the last book of Homer's Odyssey (New York: Anchor Books, 1963), p. 445.

56 Karl Kerínyi, Hermes, Guide of Souls (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1986), p. 11.

57 Rogan Taylor, The Death and Resurrection Show (London: Anthony Blond, 1985), argues that it is this theme which connects shamanism to modern showbusiness, including the circus, magicians, and musical superstars. It is also interesting that the earliest known record of a performance of magic as entertainment dates from the Twelfth Dynasty in Egypt (1991-1786 B.C.E.) and reports a command performance at court by a magician named Dedi. His tricks included the apparent decapitation and restoration of birds and animals. The Westcar Papyrus which provides details is in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. See Anne King, 'Dedi Revisited,' The Magic Circular (Magazine of the Magic Circle of London), Vol. 89, No. 957 (October 1995), pp. 182-184.

58 'A Study in the Process of Individuation,' CW 9i, para. 553.

59 At least three books written by former students at the Zürich Jung Institute are currently available: Irene Gad, Tarot and Individuation: Correspondences with Cabala and Alchemy (York Beach, ME: Nicolas-Hays, 1994); Kenneth D. Newman, The Tarot: A Myth of Male Initiation (New York: Quadrant, 1983) a book based on his Zürich diploma thesis; and Sallie Nichols, Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey (York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, 1980).

60 'Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious,' CW 9i, para. 81.

61 In addition to being mentioned in the books by Gad, Nichols, and Newman, mentioned above, these claims are also critically discussed in Stuart Kaplan, The Encyclopedia of Tarot (New York: U.S. Games Systems, 1978).

62 See Newman, p. 5, for details.

63 Newman, pp. 5-6.

64 Bernd Mertz, Kartenlegen: Wahrsagen mit Tarot-, Skat-, Lenormand- und Zigeunerblìttern (Niederhausen: Falken, 1985), p. 57. My translation.

65 The entry for 'gold' in The Herder Symbol Dictionary, translated by Boris Matthews, (Wilmette, Illinois: Chiron Publications, 1986), p. 87, connects gold with nobility and eternity, with insight and knowledge (especially esoteric), and with heavenly light in medieval paintings. Note that Hermes' wand was also golden.

Mystic Gambler Charts

66 Cf. Elisabeth Haich, The Wisdom of the Tarot (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1975), p. 27.

67 Joseph Kaster, Putnam's Concise Mythological Dictionary (New York: Perigee Books, 1990), p. 79.

68 Newman, p. 8.

69 Newman, p. 8. But Newman also admits that the only place he has found this label is in an unpublished lecture by H. K. Fierz, 'The Archetypal Image as a Healing Factor. Stuart Kaplan's two-volume reference work, The Encyclopedia of Tarot (New York: U.S. Games Systems, 1978) mentions many different labels for the magician card but 'The Gambler' is not one of them.

70 Newman, p. 8.

71 Kaplan, vol. 1, p. 245.

72 Kaplan, vol. 1, p. 49.

73 Kaplan, vol. 1, p. 137.

74 Newman, p. 120, n. 1.

75 Joseph Campbell, 'Symbolism of the Marseilles Deck,' p. 11, in Joseph Campbell and Richard Roberts, Tarot Revelations (San Anselmo, CA: Vernal Equinox Press, 1979).

76 See, for example, Arthur Edward Waite, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot: Being Fragments of a Secret Tradition under the Veil of Divination (New York: University Books, 1959).

77 Newman, p. 8.

78 Grillot de Givry, Witchcraft, Magic & Alchemy (New York: Dover Publications, 1971), pp. 296-297.

79 The information in this paragraph is based largely on pp. 111-114 in James Gollnick, 'Merlin as Psychological Symbol: A Jungian View' in James Gollnick (ed.), Comparative Studies in Merlin from the Vedas to C.G. Jung (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1991), pp. 111-131.

80 Heinrich Zimmer, 'Merlin' Corona, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1939), p. 134, comments on this Merlin's being at home in the woods, or 'enchanted forest' as showing his connection to 'the dark part of the world. One is reminded, of course, of the opening lines of Dante's Divine Comedy as well.

81 Gollnick, p. 112. See also the discussion of this issue in Geoffrey Ashe, 'Merlin in the Earliest Records,' in The Book of Merlin (London: 1988), pp. 31-42.

82 Leona Goodrich, Merlin (New York, 1987).

83 Nikolai Tolstoy, The Quest for Merlin (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1985).

84 Summarized in Gollnick, pp. 117-118. See also Alexandre Micha, ?tude sur le 'Merlin' de Robert de Boron (Geneva, 1980), especially pp. 184-185.

85 Gollnick, p. 118.

86 'The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales,' CW 9i, para. 413, 415.

87 Marie-Louise von Franz, 'Le Cri de Merlin,' in M.-L. von Franz, C.G. Jung: His Myth in Our Time (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons: 1975), p. 275.

88 Entry for 'Lady of the Lake' in Margaret Drabble (ed.), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 5th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 543.

89 'On the Psychology of the Trickster-Figure,' CW 9i, para. 485.

90 'The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales,' CW 9i, para. 440.

91 von Franz, pp. 269-287.

92 C.G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (London: Fontana Press, 1995), p. 255. [First published in 1961.]

93 Houdini identified with America and tried to erase his European roots. He claimed to have been born in Appleton, Wisconsin, and many references sources list this as his birthplace (the 14th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published in 1960, does this, for example Vol. 11, p. 800). Recent scholarship agrees, however, that he was born in Hungary. See, for example, in addition to more recent editions of the Britannica, the 'Houdini' entry in The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia (New York: Avon Books, 1983), p. 390.

94 'An ardent debunker of spiritualistic 'mediums,' he exposed their methods in Miracle Mongers and Their Methods (1920) and A Magician Among the Spirits (1924). Benít's Reader's Encyclopedia, 3rd ed., (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), p. 462.

95 Rogan Taylor, The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar (London: Anthony Blond, 1985), p. 144.

96 R. Fitzsimons, Death and the Magician: The Mystery of Houdini (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1980), p. 64.

97 Taylor, pp. 144-145. In a footnote to this passage, Taylor refers the reader to A. Hultkranze, Spirit Lodge: A North American Shamanistic Seance in Carl-Martin Edsman, ed., Studies in Shamanism (Stockholm: Almquist and Wiksell, 1967), pp. 40-42.

98 Taylor, pp. 145, 150.

99 Taylor, p. 147.

100 One expression for such an experience is being 'in the flow. Another is 'in the Tao.'

101 Bob Neale, 'The Gifts of McBride,' M-U-M (the magazine of the Society of American Magicians), Vol. 84, No. 11, April 1995, p. 15.

102 Taylor, p. 150.

103 Raimund Fitzsimons, Death and the Magician: The Mystery of Houdini (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1980).

104 Eugene Burger, The Experience of Magic (New York: Kaufman and Greenberg, 1989), p. 119.

105 Burger, p. 119.

106 Ruth Brandon, The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini (London: Secker & Warburg, 1993), p. 241.

107 J.C. Cooper, An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978), p. 187.

108 Bronislaw Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion (New York: Anchor Books, 1954), p. 71. Another interesting discussion of this practice is in Henri F. Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry (New York: Basic Books, 1970), pp. 35-37. A rather detailed analysis of this and similar shamanistic practices is Chapter IX, 'The Sorcerer and His Magic,' in Claude Lívi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1963), pp. 167-185.

109 Described as 'divination by the wand' in Nigel Pennick, Secret Games of the Gods: Ancient Ritual Systems in Board Games (York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1989), p. 16.

110 See the entry on 'rhabdomancy' in Max Maven, Max Maven's Book of Fortunetelling (New York: Prentice Hall, 1992), pp. 207-212, for a more complete discussion of this issue.

111 Joe Lantiere, The Magician's Wand: An Illustrated History (Oakville, Connecticut: Joe Lantiere Books, 1990), p. 30.

112 Jung once referred to 'Moses' rock-splitting staff, which struck forth the living water and afterwards changed into a serpent ....' and added in a footnote: 'The caduceus corresponds to the phallus. 'A Study in the Process of Individuation,' CW 9i, para. 533.

113 William Willeford, The Fool and His Scepter (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1969), p. 11. And on page 37, in connection with an illustrations of nine such baubles, Willeford comments on those baubles which are topped by a head with ass's ears or the cockscomb, which 'link the figures to animals famous for their sexuality as well as their silliness. The figures represent the intelligence of the phallus a counterpart, on the level of instinct, to the reason of the head.'

114 Monica Sjoo and Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth (New York: Harper and Row, 1987).

115 Sjoo and Mor, p. 121.

116 Sjoo and Mor, p. 145.

117 According to Marie-Louise von Franz, 'He [Jung] had dreams that he should become a woman that is the old archetypal dream of the shaman who wears woman's clothes, to integrate the other sex and descend into the other world. Quoted in Stephen Segaller and Merrill Berger, The Wisdom of the Dream: The World of C.G. Jung (Boston: Shambhala, 1989), p. 119.

118 See Morton Smith, Jesus the Magician (New York: Harper, 1978), Ludwig Blau, Das Altjüdische Zauberwesen (Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1974), pp. 29-30, and Christa Habiger-Tuczay, Magie und Magier im Mittlealter (München: Diederichs, 1992), esp. pp. 39-43.

119 'Catalogo del Museo Sacro IV,' (Vatican City: Vatican Publications, 1959), Catalog 31, p. 5, plate 5.

120 Lantiere, pp. 44-48, provides photographs and descriptions of many such wands.

121 Jung writes: 'An archetypal content expresses itself, first and foremost, in metaphors. 'The Psychology of the Child Archetype,' CW 9i, para. 267. [An earlier translation of this sentence uses 'figure of speech' rather than 'metaphor. See Russell A. Lockhart, Words as Eggs: Psyche in Language and Clinic (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1983), p. 106.]

122 C.G. Jung, Letters, Vol. 1 (1906-1950), (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), p. 376. Letter of 20 August 1945, to Karl Kerínyi.

123 The Herder Symbol Dictionary, Boris Matthews, trans. (Wilmette, Illinois: Chiron Publications, 1986), p. 1.

124 Aryeh Kaplan, Sefer Yetzirah: The Book of Creation In Theory and Practice (York Beach, ME: Weiser, 1990), p. xxi. My thanks to Edwin Wise for referring me to this source.

125 See the entry 'Sator Arepo' in The Herder Symbol Dictionary, p. 165.

126 Rogan Taylor, The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar (London: Anthony Blond, 1985), p. 136.

127 Bart Whaley, Who's Who in Magic: An International Biographical Guide from Past to Present (Wallace, ID: Jeff Busby Magic, 1991), p. 162.

128 Personal communication from Istvan Mikola, Hungarian linguist. My thanks to him.

129 My thanks to Bruce Barnett, Frederick Ferrí and Jeanine Ariana for helping me with the research on this particular 'magic word.'

130 'Transformation Symbolism in the Mass,' CW 11, para. 442.

131 Letter to Horst Scharschuch, 1 September 1952, Letters, Vol.2 (1951-1961), (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), p. 82.

132 Malinowski, p. 73.

133 Malinowski, p. 75.

134 Hans Dieter Betz (ed.), The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), Table of Spells, pp. xi-xxii.

135 Eugene Burger and Robert E. Neale, Magic and Meaning (Seattle, WA: Hermetic Press, 1995), p. 177.

136 The Herder Symbol Dictionary, trans. Boris Matthews. (Wilmette, Illinois: Chiron Publications, 1986), p. 40.

137 Reprinted in Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth (New York: Doubleday, 1988), p. 215.

138 See the entry 'Bann' in Handw–rterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens (Berlin: 1927), Volume I, pp. 873-880.

139 The Tavistock Lectures, CW 18, para. 409.

140 Ad de Vries, Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery, 2nd ed. (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Co., 1976), p. 100.

141 Psychology and Alchemy, CW 12, para. 219.

142 Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, The Magician Within: Accessing the Shaman in the Male Psyche (New York: Avon Books, 1994), p. 110.

143 Cf. Lucile H. Charles, 'Drama in Shaman Exorcism,' Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 66, No. 260 (April-June 1953), pp. 95-122.

144 Taylor, p. 40.

145 See, for example, Richard Bandler and John Grinder, ReFraming: Neuro-Linguistic Programming and the Transformation of Meaning (Moab, UT: Real People Press, 1982). Note that Bandler and Grinder's first book was called 'The Structure of Magic' (Science and Behavior Books, 1975).

146 Aion, CW 9ii, para. 25.

147 Aniela Jaffí, personal communication (1985). I am grateful to her for her friendship and support during the time I was first considering studying at the Jung Institute. She died in 1991.

148 See, for examples: Otto Lippross, Logik und Magie in der Medizin (München: J.F. Lehmanns Verlag, 1969); Gíza R¢heim, Magic and Schizophrenia (New York: International Universities Press, 1955); Rainer Wassner, Magie und Psychotherapie: Ein gesellschaftswissenschaftlicher Vergleich von Institutionen der Krisenbewìltigung (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1984).

149 Donald Kalshed, Lecture, 'ÆFitcher's BirdØ and the Dark Side of the Self,' Zürich Jung Institute, February 22, 1994.

150 'The Mana-Personality,' CW 7, para. 377.

151 'Definitions,' CW 6, para. 783.

152 C.G. Jung, 'A Talk with Students at the Institute,' in William McGuire and R.F.C. Hull (eds.), C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), p. 363.

153 CW 9i, para.525.

154 Carol Pearson, in discussing 'transformation through ritual action,' describes one therapist having 'clients visualize putting their problems on the table. She hands them a magic wand and asks them to imagine their problems magically disappearing. Carol S. Pearson, Awakening the Heroes Within (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1991), p. 203.

155 See, for example, J. Marvin Spiegelman, 'Active Imagination: Values, Limitations, and Potentialities for Further Development,' Harvest, No. 27 (1981), pp. 81-89. See also Israel Regardie, The Middle Pillar: A Co-Relation of the Principles of Analytical Psychology and the Elementary Techniques of Magic (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1970).

156 Russell A. Lockhart, Words as Eggs: Psyche in Language and Clinic (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1983), p. 85.

157 'Concerning Mandala Symbolism,' CW 9i, para. 645.

158 Richard Noll, The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 292.

159 Rogan Taylor, personal communication. My thanks to him.

160 Richard F. Smith, Prelude to Science: An Exploration of Magic and Divination (New York: Scribner, 1975), p. 24.

161 A.K. Shapiro, 'The Placebo Effect in the History of Medical Treatment: Implications for Psychiatry' (1959), quoted in Jerome D. Frank and Julia B. Frank, Persuasion and Healing, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), p. 134.

162 Michael Harner, The Way of the Shaman (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), p. 135.

163 Carol S. Pearson, Awakening the Heroes Within (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1991), p. 201.

164 The issues and possibilities here are not just theoretical. There are potential clinical uses as well. Some of these have been explored in print. See, for example, Mariann Baskin Gabriel, 'Using the Shamanic Journey in Psychotherapy,' Shamanic Applications Review: A Journal of Religious Resources in Psychotherapy, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Fall 1995), pp. 47-51, and Edward Whitmont, 'Magic and the Psychology of Compulsive States,' The Journal of Analytical Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1957), pp. 3-32. 165Psychology and Alchemy, CW 12, para. 6.

P.S. Thanks for reading this. To contact me by e-mail: jg@granrose.com

Page 3 of 3

Back to Page 2 | Back to Page 1

best utilize the features of each game.

Single-card keno is just that, a simple game with your choice of pay tables based on the number of spots you choose to mark. Your bet does not increase or decrease the short or long term odds and pays of the game.

Four-card keno allows you to play four games of keno at once where each game costs one credit to play. Obviously, your wager just increased to four times as much. Make sure you account for this in your bankroll if you decide to switch from playing single-card to four-card. You should always play four-card keno the same way you would play single-card keno. That is, the spots you feel comfortable playing on a single-card game should be the same spots you play across the four-card keno.

Multi-card keno allows the player to play up to 20 cards at the same time. Playing all the available cards will increase your wager by a factor of 20 from single-card keno. If you are used to playing single-card at one credit on a quarter machine, your bet can easily increase to $5 if you play all 20 cards at one coin.

The key to the different number of cards is understanding what happens when you start to overlap your spots on different cards. The more you overlap, the more you reduce the chances of winning across all the cards. The less you overlap, the more you increase your chances of winning across all the cards.

We won't bore you with a lot of math here, trust that as mathematicians, game designers, and slot machine experts, we know what we are talking about. Most everyone will be able to verify the following simplification of keno to illustrate our key point.

By overlapping your spots, you win less frequently, and when wins happen they pay on multiple cards. By not overlapping your spots, you win more often and pays happen on single cards only.

A 2 spot game across 9 numbers where two numbers are drawn and you win 1 credit when both of your numbers are selected. Your chances of winning are 1 in 36, your chances of losing are 35 in 36, with a long term expected return of just under 3% per credit bet.

The same game played on two cards with no overlap. Your chances of winning are 1 in 18, your chances of losing are 17 in 18, with a long term expected return of just under 3% per credit bet.

The same game played on two cards with one spot overlapping. Your chances of winning are 1 in 36, your chances of losing are 35 in 36, with a long term expected return of just under 3% per credit bet.

Your long term odds are the same the more cards you play. Your chances of having a win increase when you decrease the overlap. Your chances of having a win decrease when you increase the overlap. When a win happens, your wins will be 'larger' with more overlap because there will be more wins at the same time. Your wins are 'smaller' with less overlap because there is, generally, only one win per spin.

One of the worst examples we have seen of four-card keno play was an unfortunate soul at Casino Arizona—Indian Bend (before Talking Stick opened) who marked a line of six spots on four cards, all on the same numbers. She was basically playing single-card keno with a four credit wager!

Stay informed about the games you play, have fun, and ask us if you have any questions!

Originally Posted at Arizona Gaming Guide